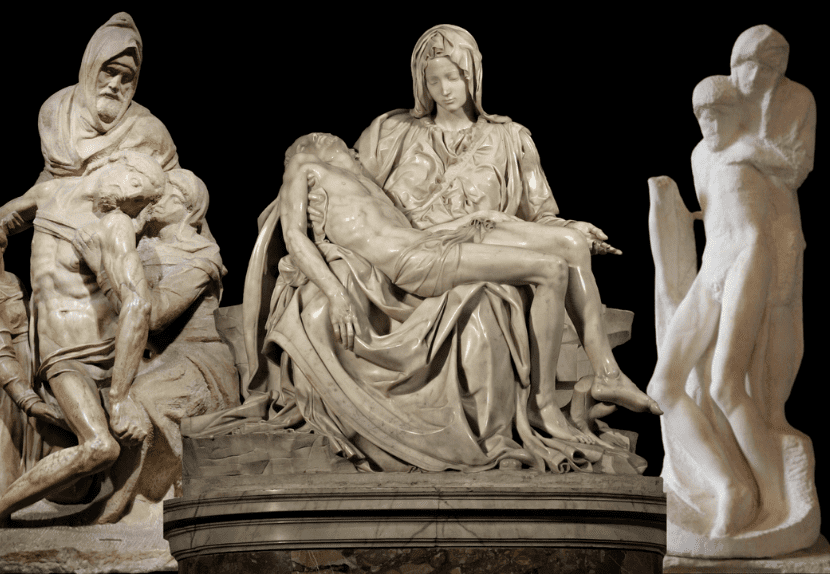

Whenever I am standing in front of Giotto’s Madonna and Child (1310 CE) in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy and discussing the naturalistic innovations introduced by the artist, I ask my students why it took so long for Medieval painters to reacquire the ability to depict subject matter in a realistic manner. The logical answer that I usually get is that artists were afraid of being punished by the church. That depicting Christian subjects as mundane and human might somehow be seen as blasphemous in a still-very-Byzantine world where Madonna’s usually looked like aliens and Baby Jesus regularly appeared with a receding hairline and five o’clock shadow.

As clear-cut an explanation as this may seem, I remind everyone that by the time we see changes take place in art, it usually means that they have already taken place in society. That the socio-philosophical game-changer of the medieval world was not an artist, but a spoiled-rich-kid from Assisi named Giovanni di Piero Bernardone, who had been nicknamed “Francesco” by his dad in honor of the lucrative business dealings he had had with textile merchants from France, known as the franceschi. After living the first have of his life in the proverbial “Fastlane” – fast cars, fast women – this second-most-penitent of penitent saints (see Mary Magdalene) had a life-altering conversion involving a talking crucifix (i.e. Jesus) in a dilapidated chapel outside of Assisi that told him to “rebuild his house which had fallen into ruin”. From that point on, Francis, the Catholic Church and the world would never be the same.

In addition to establishing one of the most important Catholic orders in history for both frati (brothers) and soure (sisters), upon whom he imposed the same vow of poverty he himself had taken; actively and passionately preaching the message of the gospels throughout the world; succoring the poor, hungry and sick – particularly lepers (see Jesus); and inventing the Christian tradition of the Christmas creche, Francis also managed to change the world. The greatest revolutionary in Western civilization since Jesus Christ (as I like to call him) suddenly began to offer an alternative existential reality to Medieval Christians – one in which the natural world was a direct reflection of the goodness of God. Since the fall of the Roman Empire (476 CE), the Catholic (or Latin Christian as it was called) Church had preached and enforced a transcendental world view. One in which anything that was not God – or otherworldly – was evil. This included the natural world around us that was considered material and therefore nothing more than distraction and temptation luring souls off the path of righteousness and salvation.

Francis instead claimed that the natural world was given to us as a gift from God, and was therefore not only good, but imbued with God himself. Nature should not be shunned and ignored, but celebrated and revered. And moreover, human beings were not here to dominate and control nature (see Genesis 1:26), but to live with it in harmony. Man was no more important than the ant and no less than the elephant. Francis did not use the word “ecosystem”, but had the word existed in the 13th century, he would have. And even as malaria and tuberculosis caught up with him late in his life and robbed him of his sight, Francis began to ecstatically sing the praises of nature in verse in his famous “Canticle of the Sun”. The sun and fire became his brothers, the moon and water his sisters (see 1960’s commune…). Diving into frozen lakes and rolling around in thorn bushes brought not pain, but instead pleasure afforded by nature, according to Francis (see “either you’re holy or you’re crazy…).

Not surprisingly, within a half century of his death in 1226, artists like Cimabue, Dante and Giotto appeared, and each reflected the little giant’s philosophy in his respective art. Cimabue, the first artist to begin to attempt to break from the abstraction of Byzantine art, painted what is still today the earliest-known portrait of the saint in the lower basilica of Assisi (see above). Dante, who was the first author to publish in the vernacular (see The Divine Comedy), described St. Francis as rising like the sun out of Assisi, in a world that was otherwise black and gloomy, in Canto XI of his Paradiso. And, of course Giotto, who was a lay member of the Franciscan Order, who best embraced the saint’s message in what I like to call his “visual vernacular” style of painting, where saints look and act a hell of a lot like regular people and their world looks pretty much like our own. And even a much more contemporary saint has kept Francis’ legacy alive when Saint JPII made St. Francis of Assisi the Patron Saint of Ecology in 1979 (see “climate change doesn’t exist…”, help us St. Francis!!!)

…But I digress… so if it wasn’t fear of punishment by the church, why did it take so long for artists to figure out how to make things look like they do in the natural world?

Stay tuned for my next blog and find out!!!

I’m sure the suspense is killing you…