In our last installment of “Why I just can’t stop talking about Giotto” we learned that “magic” rods are more effective than big ones…

That said, the middle tier of frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel depicts scenes from the childhood and mission of JC (see “Son of God”).

Here the G-Man continues his extraordinary cinematic parade of human caricatures, psychological and gender profiling, and just-plain-funny-visual social commentary.

In the Nativity (below), I find myself realizing once again, that the older I get, the more I appreciate his art. Notice how the post-partum BVM is still up and active as she adjusts the larvae-like BJC in his crib; while down below poor Joseph has lost the battle to fatigue and is conked out. And although I may sound critical or accusatory, I too almost immediately succumbed to sleep after the births of both our children, even though it was my wife who should have been the exhausted one!

“Nativity”, Giotto, 1303, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

In the Flight into Egypt (below), Giotto depicts perhaps the happiest donkey in the history of art, which is understandable considering its load! The side-saddle position of the BVM is absolutely charming.

“Flight into Egypt”, Giotto, 1303, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

Yet, it is Giotto’s exceptional rendering of motion that is the most palpable aspect of the painting, particularly in an early 14th-century world where static icons still dominated the visual arts. A left-to-right motion that is achieved through the strict-right-side-profile positioning of the figures, the sloping-fish-fin-type hill in the background, and if you’re still not getting it, the traffic-cop angel in the upper right who seems to gesture “keep it moving people, keep it moving”!

But the most profound aspect of the painting is how Joseph’s robe on the far right and the last figure on the far left disappear beyond the border of the painting, insinuating a continuous space beyond the picture frame and as if we were seeing the figures in a clearing. Giotto is suggesting that the painting is not a finite thing, nor a single moment in time, but instead part of a larger time/space continuum; and that if we just keep looking, all the figures would gradually disappear out of frame stage right…

I REPEAT: MOST ARTISTS AT THIS TIME WERE STILL STRUGGLING TO MAKE PEOPLE LOOK LIKE PEOPLE, WHILE GIOTTO WAS INSTEAD DEPICTING REALITY THROUGH A VERY-MODERN-LOOKING CINEMATIC LENS!!!

“Wedding Feast at Cana”, Giotto, 1303, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

In a later scene, Giotto depicts JC’s first public miracle at the Wedding Feast at Cana (above). The story is worth revisiting. While JC and the BVM were at a wedding celebration, the worst imaginable thing occurs – the hosts run out of wine! Having heard this story so many times, the gravity of the disaster is somewhat watered down (pun intended) to modern ears. In order to allow my undergrads to truly grasp the meaning of this story, I ask them what they did at the last collegiate party they attended where there was no longer any beer. The unanimous response – “we left”! In fact, I think just about anyone (yours truly included) would leave a dry wedding. So, Mary turns to JC, who she knows is “special”, and asks if there was something he could possibly do to help the embarrassed hosts. JC responds in a solemn tone, “Woman… my time has not yet come”, meaning that he and GTF (see “God the Father”) had a preordained plan of when JC would go public with his miraculous powers – and this was not the moment! So, Mary turns to her son again and repeats more sternly “DO YOU THINK THAT YOU CAN DO SOMETHING ABOUT THIS?”; to which JC responds, “ok” and performs his greatest party trick, as water is turned into wine. The moral of the story – OBEY YOUR MOTHER!! That even JC was willing to break with divine protocol in order to make mamma happy!

In his painting of the subject, Giotto’s inserts an absolutely hilarious caricature in the person of the large, jolly fellow dressed in orange to the far right of the scene (below). What else could he be if not the winetaster (see sommelier), as his large bulbous belly is juxtaposed against the large bulbous amphora – both of which are effective containers of wine! I like to call him the Norm Peterson (see 1980s Boston-based-Emmy-award-winning sit-com) of medieval art. It has, in fact, been proposed that this figure is actually a self-portrait of the G-Man. We will probably never know for sure, but for some reason, I could indeed accept that it is. This looks like a fun guy with whom to hang out, which is how I have always imagined Giotto.

“Wine Taster”, Giotto, 1303, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

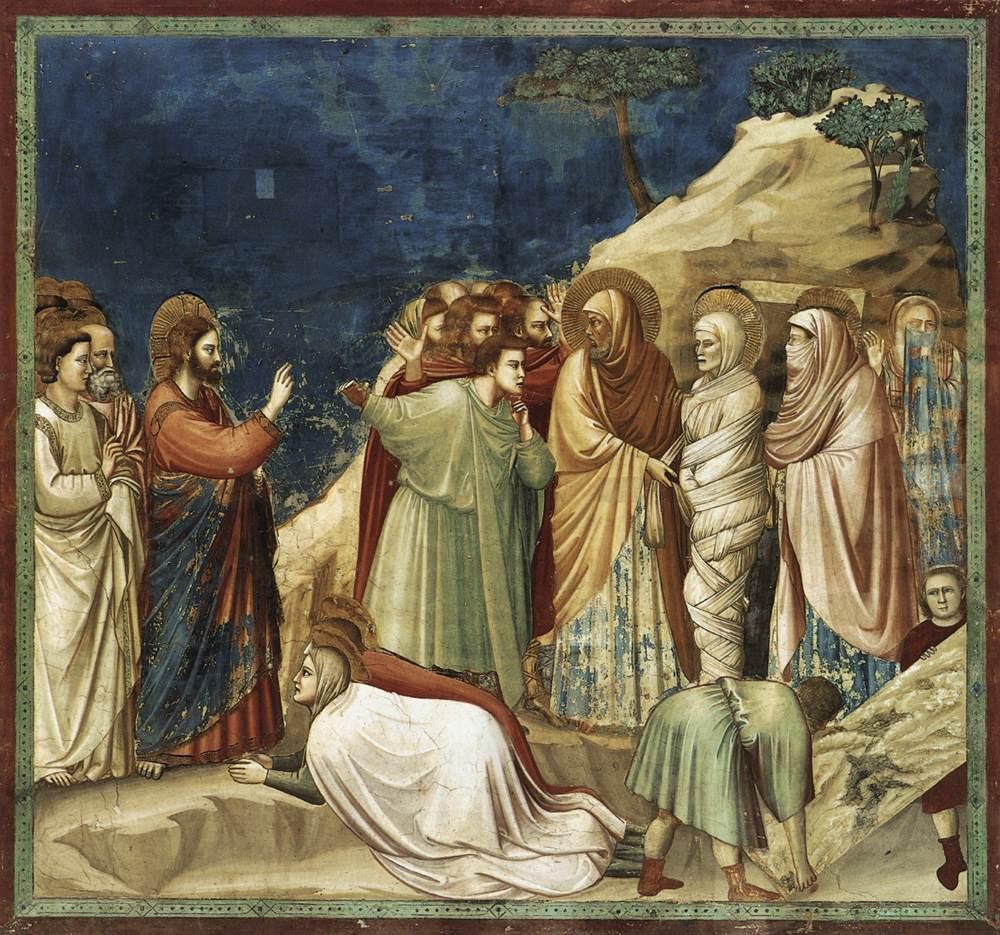

In his Raising of Lazarus (see title image), Giotto joins the ranks of only a handful of artists (see T.S Elliot) in achieving that most sophisticated of sensory effects, known as interchangeability of the senses. That is, evoking one sense using another – a smell through a visual image, a tactile sensation through a sound, a visual image through a taste…

According to the Gospel of John, a good friend of JC named Lazarus had died. After four days, JC went to the place where he was entombed and asked for the tombstone to be moved and the tomb opened. I believe that it was here that the exclamation “Jesus Christ” came into existence. The person next to JC said “Jesus Christ!… He’s been in there for four days!” … and history was made.

The figures to the right of the tomb cover their faces with their robes in anticipation of the putrefied stench emanating from a person who has been dead for four days (below). In the 14th century, that smell would have been a very familiar to everyone, as it is even today in many parts of Italy. I have uneasy childhood memories of visiting my family in southern Italy and frequenting wakes in the homes of the deceased, which were usually held only hours after their deaths. Funerals were usually held the following day, as loved ones raced against the clock of organic decomposition.

By simply showing figures covering their noses, Giotto triggers a familiar albeit ghastly olfactory sensation that would have his audience cringing and their stomachs turning!!

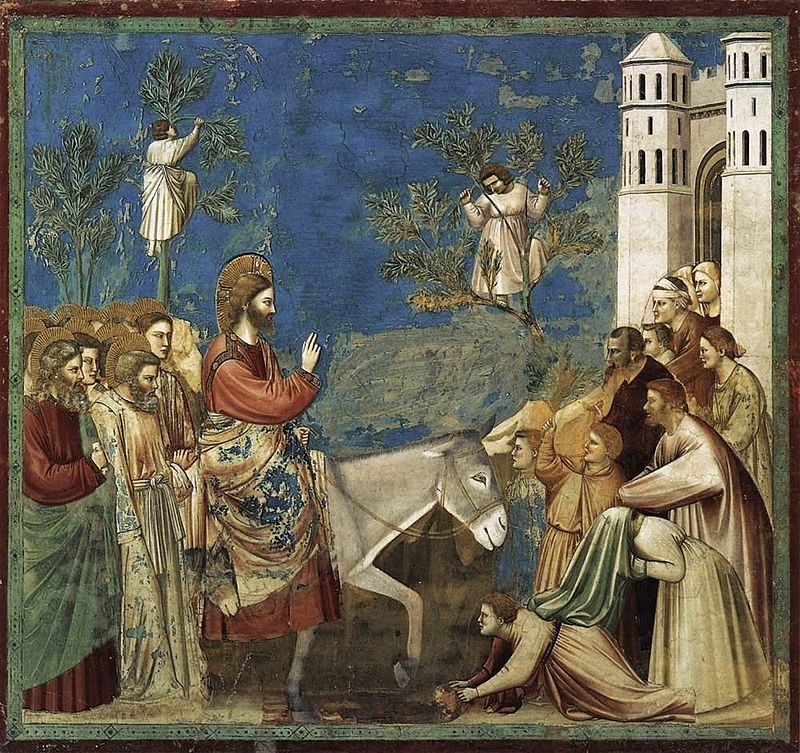

The Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem (below) kicks off the last series of scenes in the chapel, which depict the Passion of Jesus Christ. In the painting, it looks as if JC went back to the same rental donkey company that his parents used in the earlier Flight into Egypt scene (see reusing same donkey cartoon). It also worth noting that in Italy olive branches paradoxically substitute palm branches on Palm Sunday (see the olive trees in the background).

“Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem”, Giotto, 1303, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

But the most stunning and “was-Giotto-an-alien-someone-call-the-History-Channel” aspect of the painting is the composition of the three figures in the lower right-hand corner (below). Three separate figures performing the single and sequential action of disrobing from top to bottom in order to lay its/their cloak before the Christ.

The arrangement of these three figures is the earliest attempt at animation that I know of in the history of Western art! To quote a line from the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding – “While your ancestors were living in trees, mine were writing philosophy”. Well, while the rest of art world was trying to figure out the basics of naturalism, Giotto was actually flirting with animation!!!

Moreover, Giotto was also imbuing his art with a timeless pathos which few artists in history have ever equaled.

His Kiss of Judas (below) is the stuff of iconic legend, and in this author’s modest opinion, the most powerful scene in the history of art.

“Kiss of Judas”, Giotto, 1303, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

The surreal silence of dead-of-night Gethsemane has been violated by a human tsunami. The offensive sound of the scene is palpable as a hoard of high priests, soldiers and, of course, traitors sound their horns, rattle their lanterns, shout and jeer. It is like a scene in modern movie theaters where the sound is intentionally turned to uncomfortably high levels in order to increase dramatic effect.

But if Giotto’s movie were up on the big screen, the way I imagine it is that he would zoom in on Jesus and Judas and completely drop the sound. (below) The visual background chaos would continue but would lose both its sound and significance as the viewer becomes lost in the impassive stare of the Christ looking down into the eyes of this imperfect and greedy little being who would betray all that is good and beautiful for thirty pieces of silver.

The first time that I saw this painting back in 1996, I knew I had seen that same kind of intense gaze before… and then it dawned on me (SEE BELOW!!!)

The first time that I saw this painting back in 1996, I knew I had seen that same kind of intense gaze before… and then it dawned on me (SEE BELOW!!!)

“I know it was you, Fredo. You broke my heart…” Godfather II

Now, me telling you that Francis Ford Coppola was inspired by Giotto in composing this historic scene is probably hyperbole, but that fact that I can successfully compare an early 14th-century painting to a 20th-century film is absurd. But there it is for all to see.

And that, my friends, is why the G-Man sits atop my Olympus of artists…